|

Lewis and Clark statues in Jefferson City, Missouri, featuring from left to right:

York, Meriwether Lewis, Seaman (dog), William Clark, and George Drouillard.

Lewis & Clark on the Jefferson River

A Narrative of their travels at the Missouri Headwaters

By Thomas J. Elpel

Little was known about North America west of the Mississippi at the beginning of the 1800s. The Missouri River flowed east, merging with the Mississippi en route to the Gulf of Mexico, while the Columbia flowed west from a similar latitude and spilled into the Pacific Ocean. It was thought that there might be a navigable water route with a low portage connecting these two rivers to facilitate commerce across the continent.

During 1804 and 1805 the Corps of Discovery, commanded by co-captains Meriwether Lewis and William Clark, traveled more than 4,000 miles by foot, canoe, and horseback from Saint Louis up the Missouri River, across the Rocky Mountains and down the Columbia to the Pacific Ocean. The following year they traveled all the way back home.

It was an eclectic group, with the two captains, Clark's slave York, the teenage Indian woman Sacagawea with her infant son, and Lewis' dog Seaman, plus numerous soldiers, hunters, boatmen, and French trappers. Their adventures became one of the world's greatest exploration stories, documented through the journals of Lewis and Clark and the men.

The Louisiana Purchase

England, France, and Spain had competing claims on the American interior throughout the 1700s, a competition that ultimately helped the United States gain her freedom and her size. England won control of the upper Mississippi and Northwest Territories from France in the French and Indian War of the 1860s. England wanted to reserve these lands for a fur trade monopoly and therefore forbid American colonists from settling west of the Appalachians. This settlement restriction was a contributing factor to the American Revolutionary War.

Spain and France aided the colonists in the Revolution, believing that if the Americans won, they would form a weak new country, easy to control on the Atlantic coast. England would also be weakened, so France and Spain could expand their hold on the American interior.

But when the war ended and the United States was born, England opted to cede the Mississippi basin to the new American country to prevent it from falling into the hands of Spain or France. Suddenly, the new United States of America was a powerhouse, twice its former size, and settlers were already bumping up against the Louisiana Territory. Spain closed the port of New Orleans and the Mississippi River to U.S. shipping, trying to cripple the new country, but eventually bowed to diplomatic pressure in 1795 to re-open the port. Spain had neither the money nor the manpower to defend the Louisiana Territory from American expansion and turned it over to France's Napoleon Bonaparte in 1800, believing the French could defend it.

Napoleon hoped to isolate England, and Americans still resented England from the recent war, but Americans also felt threatened having France on its western frontier and in control of the port of New Orleans. President Thomas Jefferson threatened to rejoin its adversary of the recent Revolutionary War and move against the French, which would have defeated Napoleon's attempts to isolate the Mother country.

Jefferson used a carrot and stick approach, suggesting a peaceable alternative in that the U.S. could buy the port of New Orleans to guarantee passage of commerce down the Mississippi to the Gulf of Mexico. Congress gave its approval to offer Napoleon $2 million for the purchase, with flexibility to spend up to $9,375,000 if necessary, then sent James Monroe to France in 1803 to negotiate a deal. However, instead of accepting the $2 million offer, Napoleon counter-offered to sell the entire Louisiana Territory to the U.S. for $15 million, doubling again the size of the United States. There was no way to communicate efficiently with the President or Congress from overseas, so Monroe and the U.S. ambassador to France, Robert Livingston, agreed to the deal, and obtained approval for it after the fact. With the agreement in place, Napoleon announced, "This accession of territory affirms forever the power of the United States, and I have just given England a maritime rival that sooner or later will lay low her pride."

Replica keelboat at Lewis and Clark State Park, Iowa.

Preparing for the Expedition

Planning for the Lewis and Clark expedition began prior to the Louisiana Purchase as a proposal to explore foreign territory. In the winter of 1802-1803, Meriwether Lewis wrote a cost estimate for the expedition, based on a party of one officer and twelve soldiers. The soldiers were already on the Army payroll, so that helped minimize costs. Lewis estimated $2,500 in material expenses for boats, scientific instruments, food, medicinal supplies, guns and ammunition, plus gifts and trade goods for Indian tribes he encountered along the way. Jefferson sent a special, secret message to Congress in January 1803 asking for the appropriation. This was just a week after Congress approved his plan to offer to buy the port of New Orleans. Nobody imagined at the time that Napoleon would part with the entire Louisiana Territory.

Meriwether Lewis, then twenty-nine years old, began preparing in earnest for the expedition as soon as it was approved by Congress. Jefferson sent him to study with experts in the sciences, map-making, and medicine. Lewis studied intensively for six months while also ordering supplies for an expedition, which soon began to grow in the number of men and the amount of supplies.

In addition to the appropriation from Congress, this was a military operation, and Lewis was authorized to collect arms, ammunition, and other supplies from Army outposts, or to have them manufactured at the U.S. Army Arsenal. Furthermore, Jefferson supplied Lewis with a letter of credit, since the expedition would be unable to communicate with the President or Congress, and would probably be nearly out of supplies when it reached the Pacific Ocean. With the letter of credit, Lewis could hire interpreters, book passage on a ship back to the U.S. from the Pacific (if they encountered one), or buy supplies from merchants or trappers along the way.

It was probably the most open-ended letter of credit ever issued by the United States government, authorizing Lewis to buy anything he wanted and to bill it to any agency of the U.S. government anywhere in the world. The size and cost of the expedition continued to grow.

It was Lewis's expedition to command, however, he asked Jefferson for permission to bring his friend William Clark, thirty-three, as a co-captain. Lewis had spent only six months with Clark when serving under him in the Army, but in that time they found great friendship and respect for each other's abilities. Jefferson consented to the arrangement, although it was highly unusual. An expedition with two captains can be a recipe for disaster, allowing differences of opinion to divide the group. Unfortunately, when the paperwork came through, Clark was given the rank of lieutenant, leaving Lewis in command. But Lewis and Clark decided not to tell their men. They treated each other as co-captains throughout the expedition.

To assemble a party, they were authorized to select officers of their choice from several army bases, and they were careful to pick the best of the best--soldiers who were hard working, ambitious, disciplined, and especially those who were comfortable on the frontier.

On July 4, 1803, the nation first learned about the Louisiana Purchase, an event that greatly elevated the need for the expedition. The new territory included the western half of the Mississippi drainage from the Gulf of Mexico to the northernmost tributaries of the Missouri and west to the continental divide--boundaries that no known Westerner had ever seen. Lewis left Washington the next day, gathering supplies as he headed west to begin the expedition.

He previously designed and ordered a fifty-five foot keelboat in Pittsburg, which should have been completed by July 20th, but it wasn't done until August 31st, by which time the water level was so low in the Ohio River that Lewis and his men often had to hire pioneers with livestock to drag the boat over the riffles.

Lewis also bought two pirogues--flat-bottomed rowboats--to help haul gear down the river. On October 15th they arrived in Clarksville, Indiana Territory, and met up with Captain William Clark, the first time they had been together in person since serving together in the Army eight years earlier.

In addition to the soldiers chosen for the mission, Jefferson personally authorized Lewis to hire anyone else that might benefit the expedition. Lewis hired frontiersmen, hunters, interpreters and boatmen, plus he brought along his black Newfoundland dog named Seaman. Clark also hired men for the journey and brought along his lifelong slave, York. There was no shortage of applicants. One enlisted man boasted of being chosen for his physical conditioning when a hundred others were dismissed.

Lewis and Clark arrived at the confluence of the Ohio and the Mississippi Rivers on November 13, 1803 with about twenty men. A week later they started up the Mississippi for Saint Louis. It is believed that after a single day of paddling upstream against the mighty Mississippi that Lewis and Clark realized they were woefully undermanned and decided to double the size of the expedition and buy twice as many supplies.

Lewis and Clark arrived in Saint Louis in December 1803 with a fifty-five foot keelboat armed with a swivel gun, plus two smaller six-man boats called pirogues, and part of their crew. They built an encampment upstream from town at the mouth of the Wood River. The co-captains spent the rest of the winter hiring men and buying supplies with Jefferson's letter of credit.

Controlling a crew who had little to do all winter proved challenging. The men occasionally found nearby sources of alcohol. Fights and insubordination were common, but they made it through the winter. By May 22, 1804 they had a party of about forty-eight men, fully stocked with provisions, and finally began their journey. Lewis named the expedition the Corps of Discovery. The cost of the expedition, not counting special grants made by Congress after their return, totaled $38,722.25.

The Journeying Home exhibit at the Mead / Dakota Territorial Museum in Yankton, South Dakota.

To the Mandans

British Traders from Canada previously determined the latitude and longitude of the friendly Mandan villages on the Missouri River in today's North Dakota, but little was known about the Missouri River between there and Saint Louis. The Corps of Discovery spent the summer and fall of1804 paddling, poling, and towing their boats slowly up the Missouri River, while also making maps, documenting new species, and meeting with Indian tribes along the way. On August 19, 1804, Sergeant Charles Floyd suddenly fell ill, then died the following day of what is believed to have been a ruptured appendix. He was buried on Floyd's Bluff near today's Sioux City, Iowa. Sergeant Floyd was the only member of the Corps of Discover to die on the expedition.

Lewis tried to establish peaceful relationships with the Indians and convinced some chiefs to travel back to Washington to meet the President. Other encounters nearly led to bloodshed. In a standoff with the Teton Sioux, the expedition faced more than one hundred warriors with bows and arrows on horseback. The Indian chief eventually backed down and the expedition proceeded upriver.

Lewis and Clark passed several deserted Mandan villages, which were abandoned due to decimation of the population from smallpox. But they arrived at a thriving community on October 26. There were five earthlodge villages of Mandan and Minitari (Hidatsa) Indians with a combined population of about 4,400. The expedition built their own Fort Mandan three miles downriver from the nearest village, a place to stay and wait out the winter. They moved into the fort in November and completed it in December.

Through the winter, Lewis and Clark interviewed the Indians to learn everything they could about the country upstream. They hunted with the Indians, celebrated and danced together, and played games together. The temperature often fell way below zero, at one point reaching a low of -45F.

They hired a French Canadian fur trader, Toussaint Charbonneau, as an interpreter for the expedition, but the primary benefit for the expedition was his Shoshone wife Sacagawea. Her people lived at the headwaters of the Missouri River, where Lewis and Clark would need to trade for horses to get the expedition over the continental divide to the waters that ran down to the Pacific.

Sacagawea had been captured by the Minitari Indians four years earlier. Now sixteen, she was pregnant and gave birth to a baby boy, Jean Baptiste Charbonneau, born February 11, 1805. Sacagawea and her infant son made the entire journey to the Pacific Ocean and back with the expedition and proved invaluable along the way.

The expedition's fifty-five foot keelboat was too large to continue the journey upriver, so the men cut six large cottonwood trees and hollowed them out to make dugout canoes. The ice began to break up near the end of March, and on April 7, 1805 the keelboat was sent back to Saint Louis with a crew of eleven men, plus the journals, maps, and plant and animal specimens that had been collected on the journey so far. Later the same day, Lewis and Clark and their party of thirty-one abandoned Fort Mandan and headed upstream in search of a northwest passage to the Pacific.

It took weeks to portage the heavy dugout canoes over the hills around the Great Falls of the Missouri.

(Lewis and Clark National Historic Trail Interpretive Center, Great Falls, Montana.)

Journey to the Missouri Headwaters

With six three-man dugout canoes, plus the two six-man pirogues, almost the entire party could fit in the boats, except that on this kind of a journey almost nobody did. The boats were primarily for carrying gear. The expedition rarely paddled the boats. Sometimes they poled them upstream, pushing a stout stick against the river bottom to push themselves forward. Much of the time they walked in the river or on the river bank and towed the boats upstream with ropes. Sacagawea and her son, whom Clark nicknamed "Pomp" often rode in the boats, but also frequently walked on land and collected edible roots along the way. Lewis often walked on land to gather new specimens, while Clark usually supervised the slowly moving boat party.

Throughout the plains they found more buffalo, antelope, elk, and wolves than they could count. Wild game frequently fell through the winter ice and drowned, then washed up into piles on the riverbank in the spring. In one mass of corpses they found wolves so gorged on meat that Lewis was able to walk right up to one and kill it with his spear-like espontoon.

The expedition soon discovered the fearsome plains grizzly, which had been a frequent topic of over the winter at the Mandan villages. The bears were much larger than today's mountain grizzly bears, and they had little fear of humans. With bows and arrows for weapons, the Indians frequently lost warriors to the grizzlies, even when attacking in groups. The muskets and single-shot rifles of the expedition didn't prove to be much better, and the Corps of Discovery had numerous nearly catastrophic encounters. In one incident, six hunters shot at a grizzly bear, but it still managed to chase two of the men off a twenty-foot bluff into the river. The bear went right over the bluff after them and nearly caught one of the men before it was shot dead by a hunter on the bank.

The expedition passed out of the plains into the desertlike Missouri breaks and today's Upper Missouri River National Monument, where Lewis wrote enchantingly of the white cliffs area.

The Corps of Discovery knew they would encounter a great waterfall, but what they first encountered was completely unexpected: a fork in the river not mentioned by the Indians, with two branches of nearly equal size. The expedition spent several days exploring both rivers, and most of the crew concluded that the northern branch was the Missouri, except for the captains who correctly concluded it was the southern branch. They named the northern branch the Marias River. Having consumed many supplies already, they were able to cache one of the pirogues at the mouth of the Marias River.

Proof that the captains chose the correct river came a few days later when they arrived at the Great Falls of the Missouri. It wasn't just one waterfall, but a series of five cascades spread over ten miles. The Indians traveled the area by horseback, rather than canoe. At Fort Mandan they suggested that it would require a day or so to portage the canoes around the falls, but the portage ultimately consumed three weeks of grueling, backbreaking work to complete the eighteen-mile journey amidst the prickly pear cactus, searing heat, baseball-sized hail, torrential downpours, and maddening winds. They used wooden wheels and axels under the canoes and towed them up and down hills with ropes. The men were so exhausted that at times they fell asleep standing up as they paused while pulling or pushing the canoes.

The larger white pirogue was left below the falls, so the party moved only the wooden dugout canoes. Meanwhile, Lewis had a forty-four pound iron frame that could be covered with skins to make a high-volume, very lightweight canoe. He designed it himself and had it custom-made at the U.S. Army Arsenal back at Harper's Ferry.

With a handful of men, Lewis spent two weeks assembling the canoe, which he had covered with elk and buffalo hides that were dehaired, stitched together, and waterproofed with a composition of beeswax, buffalo tallow and charcoal. Lewis needed pine pitch, but there were no pine trees nearby. Unfortunately, the composition separated from the seams the first time the boat was put in the water. The seams remained sound only on the buffalo hides where there was a small amount of hair to grip the composition, and if the entire boat had been done that way, or if it had been sealed with pitch, then the craft probably would have worked grand. But they couldn't waste any more time with the experiment, so they located some cottonwoods of suitable size and in five days hollowed our new dugout canoes for the continuing journey.

Canyon Corner on the Jefferson River. William Clark shot a bighorn sheep here on August 1, 1805.

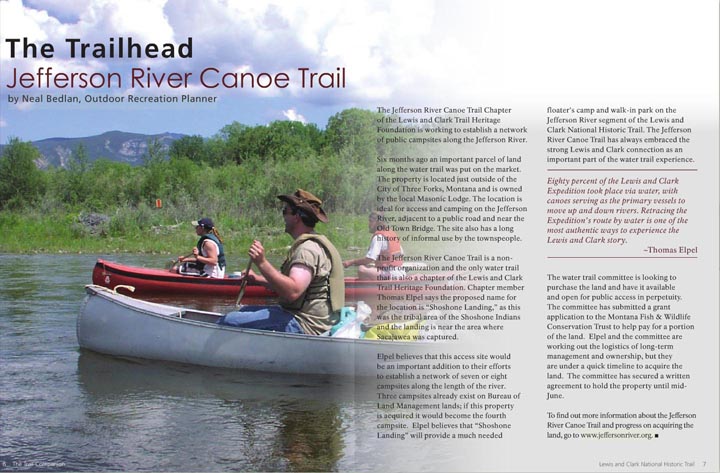

Lewis and Clark on the Jefferson River

In a month they had traveled only twenty-five miles. It was the middle of July already, and they were glad to be moving again. A few days later they encountered the towering cliffs they dubbed the "Gates of the Rocky Mountains." By the end of July they were approaching the Missouri River headwaters. Here begins a day-by-day narrative of their travels as they approached the Missouri headwaters and ascended the Jefferson River.

Thursday July 25, 1805

Lewis traveled up the Missouri with the boats. He and his men saw a large grizzly on an island, but it quickly crossed over to the mainland and ran away. They saw many geese and killed some, but generally avoided hunting these birds since it wasted ammunition and time. They killed an antelope and saw several more with their young.

On the right they passed a large creek, which they named Gass Creek, after Sergeant Gass of the Expedition. It is known as Crow Creek today.

Captain Clark set out early by foot and after a few miles arrived at the three forks of the Missouri. The plains were burnt on the north side of the river and he found a horse track that was four or five days old. Clark left a note for Lewis and followed the southwest fork of the Missouri (the Jefferson River) another twenty miles, then camped a few miles upstream from the present day town of Willow Creek, very tired, with blistered feet and wounds from prickly pear cactus. He was accompanied by Charbonneau, who was nearly lame with a bad ankle. Clark noted the abundance of red, black, yellow, and purple currants, chokecherries, Boin roche (red-osier dogwood), and red berries. He wrote, "Musquetors verry troublesom until the Mountain breeze sprung up, which was a little after night."

Friday July 26, 1805

Lewis continued up the Missouri, passing today's Sixteen Mile Creek, which they named "Howard's Creek" after the expedition's Thomas P. Howard. Lewis noted the pincushion cactus and commented on the needle-and-thread grass, "these barbed seed penetrate our mockersons and leather legings and give us great pain untill they are removed. my poor dog suffers with them excessively, he is constantly binting and scratching himself as if in a rack of pain."

Sergeant Gass wrote, "A rattle-snake came among our canoes in the water, of a kind different from any I had seen. It was about two feet long, of a light colour, with small spots all over." They also saw four deer, an otter, and a beaver, of which they killed one. Here the river was crowded with islands. In some places the Missouri was 3/4 mile wide, including all the islands. One of Lewis' men found an Indian bow, measuring about 2 feet, 9 inches long, with "nothing remarkable in it's form being much such as is used by the Mandans and Minetares &c."

Upriver, Clark left Charbonneau and Joseph Fields at camp and walked twelve miles to the top of a mountain where he had a good view of the valley ahead. He came down the mountain on the hot south face, away from the river, suffering severely from the heat and lack of water, until he found a cold spring. He took the precaution of wetting his feet, head, and hands before drinking, but still felt unwell shortly afterwards. He finally made it back to camp where Fields had killed a fawn for dinner, but Clark was so sick that he did not eat.

After dinner they started hiking back downstream to meet Lewis, until Charbonneau, who could not swim, was nearly swept away crossing a channel. Clark rescued him and they proceeded on and camped at "Eagle Rock" four miles downstream from the previous night's camp. They killed two grizzly bears on an island, and noted the immense quantity of beaver. Clark was feeling worse.

Saturday July 27, 1805

Lewis wrote, "We set out at an early hour and proceeded on but slowly the current still so rapid that the men are in a continual state of their utmost exertion to get on, and they begin to weaken fast from this continual state of violent exertion." The limestone cliffs crowded the river here and they noted a great number of bighorn sheep on the rocks. Shortly afterwards, they reached the S.E. fork of the Missouri (the Gallatin River) and the wide open valley.

Lewis and his men stopped here for breakfast while Lewis walked a half mile up the Gallatin River and then "ascended the point of a high limestone clift (now known as Lewis's Rock) from whence I commanded a most perfect view of the neighbouring country." Lewis and his men camped on the Jefferson River about 1/2 mile above its junction with the Madison. He noted the abundance of gooseberries and saw some mallard ducks. The hunters brought in 6 deer, 3 otters and a muskrat.

Although the Corps of Discovery had seen evidence of Indian activity all along the Missouri, they hadn't seen any Indians in nearly four months of travels. Lewis wrote "we begin to feel considerable anxiety with rispect to the Snake Indians. if we do not find them or some other nation who have horses I fear the successful issue of our voyage will be very doubtfull or at all events much more difficult in it's accomplishment. We are no several hundred miles within the bosom of this wild and mountainous country, where game may rationally be expected shortly to become scarce and subsistence precarious without any information with rispect to the country not knowing how far these mountains continue, or wher to direct our course to pass them to advantage or intersept a navigable branch of the Columbia, or even where we on such an one the probability is that we should not find any timber within these mountains large enough for canoes if we judge from the portion of them through which we have passed. however I still hope for the best, and intend taking a tramp myself in a few days to find these yellow gentlemen if possible. my two principal consolations are that from our present position it is impossible that the S.W. fork can head with the waters of any other river but the Columbia, and that if any Indians can subsist in the form of a nation in these mountains with the means they have of acquiring food we can also subsist."

Clark wrote, "I was verry unwell last night with a high fever & akeing in all my bones." Nevertheless, he set out in great pain with his men 8 miles across the prairie to the middle fork (Madison River) and followed it down to the forks where he met Lewis.

Clark came into camp fatigued, very sick, constipated, and with a high fever. Lewis prescribed Rush's Bilious Pills, also known as Rush's Thunderbolts, for the constipation. They decided the group should camp at the headwaters for a couple days to rest, so the men soaked their deer hides in the river for tanning the next day.

Sunday July 28, 1805

Clark was very sick all night, but felt somewhat better by morning. They discussed the three forks of the Missouri, and since the middle and southwestern forks were of equal size, decided that neither could rightfully retain the name "Missouri." They planned to ascend the southwestwestern fork and so named it the Jefferson River, in honor of President Thomas Jefferson. The middle fork became the Madison River after James Madison, while the eastern fork became the Gallatin River after Albert Gallatin.

Lewis had the men build a shelter for the comfort of Captain Clark. The men were tired, but engaged in either hunting or tanning skins and making moccasins and leggings. Joseph Whitehouse wrote, "the men at Camp has employed themselves this day in dressing Skins to make cloathing for themselves. I am employed making the chief part of the cloathing for the party." The hunters brought in 8 deer and 2 elk.

Lewis wrote, "Our present camp is precisely on the spot that the Snake (Shoshone) Indians were encamped at the time the Minneatares (Hidatsas) of the Knife R. first came in sight of them five years since. From hence they retreated about three miles up Jeffersons river and concealed themselves in the woods, the Minnetares pursued, attacked them, killed 4 men 4 women a number of boys, and mad[e] prisoners of all the females and four boys, Sah-cah-gar-we-ah o[u]r Indian woman was one of the female prisoners taken at that time ; tho' I cannot discover that she shews any immotion of sorrow in recollecting this event, or of joy in being again restored to her native country ; if she has enough to eat and a few trinkets to wear I believe she would be perfectly content anywhere."

The day was very hot and the mosquitoes more than usually troublesome (but the gnats less so). An afternoon thundershower helped cool things off.

Monday July 29, 1805

The hunters went out in the morning and returned a few hours later with four fat whitetail bucks, which they referred to as "longtailed red deer." Lewis wrote, "the hunters brought in a living young sandhill crain ; it has nearly obtained it's growth but cannot fly ; they had pursued it and caught it in the meadows. it's colour is precisely that of the red deer. we see a number of the old or full grown crains of this species feeding in these meadows. this young animal is very f[i]erce and strikes a severe blow with his beak ; after amusing myself with it I had it set at liberty and it moved off apparently much pleased with being releived from his captivity."

Lewis noted the abundance of kingfishers, mallard ducks, grasshoppers, crickets, and mound-building ants. They saw trout in the river, and tried fishing, but the fish didn't bite on any kind of bait they tried. The men spent much of the day tanning hides and making clothes. Clark felt better, but was still tired and sore all over. Lewis had him take Peruvian bark (a source of quinine), plus Clark ate much venison.

Tuesday July 30, 1805

With Clark feeling better, the expedition loaded the canoes and proceeded up the Jefferson River. Lewis hiked overland with Charbonneau, Sacagawea, and two invalids for half a day. They passed through the place where Sacagawea's people hid when she was captured. All except Lewis boarded the canoes when they met again, and Lewis continued on shore. With all the brush, beaver dams and sloughs along the river, Lewis found it impractical to stay near the water, and so separated from the group for the rest of the day. He returned to the river downstream from present day Willow Creek by nightfall and fired his gun and shouted in hopes of meeting up with the canoe party, but they did not hear him where they were camped two miles farther downriver.

Lewis killed a duck for dinner, and wrote "I found a parsel of drift wood at the head of the little Island on which I was and immediately set it on fire and collected some willow brush to lye on. I cooked my duck which I found very good and after eating it layed down and should have had a comfortable nights lodge but for the musquetoes which infested me all night. late at night I was awakened by the nois of some animal runing over the stoney bar on which I lay but did not see it ; from the weight with which it ran I supposed it to be either an Elk or a brown bear (grizzly). the latter are very abundant in this neighborhood. the night was cool but I felt very little inconvenience from it as I had a large fire all night."

Wednesday July 31, 1805

Lewis wrote, "This morning I waited at my camp very impatiently for the arrival of Capt. Clark and party ; I observed by my watch t[h]at it was 7. A. M. and they had not come in sight. I now became very uneasy and determined to wait until 8 and if they did not arrive by that time to proceed on up the river taking it as a fact that they had passed my camp some miles last evening. just as I set out to pursue my plan I discovered Charbono walking up shore some distance below me and waited until [he} arrived I now learnt that the canoes were behind, they arrived shortly after. their detention had been caused by the rapidity of the water and the circuitous rout of the river. they halted and breakfasted after which we all set out again and I continued my walk on the Stard shore"

The canoe party passed by Philosophy River (Willow Creek) where Clark camped on the night of of July 26. Lewis noted that this river split and reached the Jefferson in seven separate streams. The area was rich with timber and vast numbers of beaver and otter. In the uplands Lewis observed that the soil was poor and the grass was so dry that it would burn like tinder.

Just before camping in the evening, George Drouillard saw a grizzly enter a thicket on the left side of the river. The men surrounded the thicket, but never found the bear. Lewis wrote: "nothing killed today and our fresh meat is out. when we have plenty of fresh meat I find it impossible to make the men take any care of it, or use it with the least frugalility. tho' I expect that necessity will shortly teach them this art."

Sergeant Gass slipped and fell backwards, injuring his back on the canoe. The entire expedition camped together at the mouth of present day Antelope Creek.

Thursday August 1, 1805

Lewis set out overland in search of Sacagawea's people with the two interpreters Drouillard and Charbonneau, along with Sergeant Gass, who was too lame to work the canoes, but well enough to walk. They climbed the dry hills through what is now Lewis and Clark Caverns State Park, hoping to take a northwesterly shortcut to the Jefferson River, based on previous observations by Captain Clark.

Lewis had taken a dose of glauber salts in the morning to treat a slight case of dysentery that had bothered him for a few days. The medicine, along with the 11-mile hike through the hot hills without water, nearly exhausted Lewis before they reached water again. They never discovered the caverns, and their "shortcut" brought them instead to today's Boulder River, which they called Field's Creek in honor of Reubin Fields of the expedition. The Jefferson took a more southwesterly course.

The men saw a herd of elk at the river, of which Lewis and Drouillard killed two. They were delighted to have fresh meat after a couple days without any, except a single beaver. They cooked and ate, leaving the rest for Captain Clark and the crew to find as they came upriver. Lewis and company hiked another six miles and camped on the right side of the river.

Downstream, Captain Clark and the rest of the men brought the canoes and gear up through the narrow and rugged canyon, struggling against the swift water all the way. Joseph Whitehouse recorded, "the hills higher and more pine and ceeder timber on them. we passed high clifts about 500 feet high in many places. considerable of pine on the Sides of the hills all the hills rough and uneven. at noon Capt. Clark killed a mountain Sheep, on the Side of a Steep redish hills or clifts the remainder of the flock ran up the Steep clifts. the one killed roled down Some distance So we got it and dined eairnestly on it. it being Capt Clarks buthday he ordered Some flour gave out to the party." He added, "I left my Tommahawk on the Small Island where we lay last night which makes me verry Sorry that I forgot it as I had used it common to Smoak in." The tomahawk had a hollow handle, which served as a smoking pipe.

They passed by today's South Boulder River, which they named Frazier's Creek after Rob Frazier of the expedition. A few miles later they found the two elk left by Lewis, and Jo and Reuben Fields shot five deer. Clark saw a large bear eating currants, but did not get a shot at it. They camped on the left bank, opposite from the Boulder River.

Friday August 2, 1805

Captain Lewis felt much better. He and his overland party resumed their march at sunrise and waded across to the left bank of the Jefferson River for a shorter route through the valley. He wrote, "soon after passing the river this morning Serg. Gass lost my tommahawk in the thick brush and we were unable to find it, I regret the loss of this usefull implement, however accidents will happen in the best of families, and I consoled myself with the recollection that it was not the only one we had with us."

Lewis described the Jefferson Valley, saying "the plain ascends gradually on either side of the river to the bases of two ranges of high mountains (the Tobacco Roots and the Highlands), which lye parallel to the river and prescribe the limits of the plains. The tops of these mountains are yet covered partially with snow, while we in the valley are nearly suffocated with the intense heat of the mid-day sun ; the nights are so cold that two blankets are not more than sufficient covering."

They found "great quantities of currants today, two species of which were red, others yellow, deep perple and black ; also black gooseberries and serviceberries now ripe and in great perfection. We feasted sumptuously on our wild fruits, particularly the yellow currant and the deep perple serviceberries, which I found to be excellent."

They saw many antelope and killed two deer. They also saw lots of elk and bear tracks, plus very old buffalo bones and manure. Some of the beaver dams along the river were five feet high and backed water up over several acres. There were no recent signs of Indians, but they found abandoned conical lodges of willow boughs and brush, built with a door on one side. Lewis and company hiked twenty-four miles before camping on the left side of the river near the present day community of Waterloo.

Captain Clark and his men meanwhile continued upriver struggling with utmost exertion against the rapidity of the current to drag the canoes and gear upstream. There were many islands in this part of the river, both large and small. They saw mallard and redheaded ducks, black woodpeckers, a large herd of elk, and several rattlesnakes.

On the right side they passed by the mouth of Birth Creek named for Clark's birthday of August 1st. It is now known as Whitetail Creek. Clark covered 17 miles and also camped on the left bank of the Jefferson River near the present day Kountz Bridge. He wrote, "I have either got my foot bitten by Some poisonous insect or a tumer is riseing on the inner bone of my ankle which is painfull."

Saturday August 3, 1805

Lewis and his overland party set out before sunrise and continued their march along the left side of the river. At about 11 a.m., Drouillard killed a doe, and they stopped for two hours to rest and eat breakfast. Later they "passed through a high plain for about 8 miles covered with prickley pears and bearded grass, tho' we found this even better walking than the wide bottoms of the river, which we passed in the evening ; these altho' apparently level, from some cause which I know not, were formed into meriads of deep holes as if rooted up by hogs ; these the grass covered so thick that it was impossible to walk without the risk of falling down at every step." They walked until dark, and camped near today's town of Twin Bridges, covering about twenty-three miles for the day.

Downstream, Clark and his men continued their arduous task of pulling the canoes and gear upriver against the current, where they frequently had to "double man" the canoes to drag them one-at-a-time over the shallow riffles of stone and gravel. Clark killed a deer in the morning, and along the way found the tracks of an Indian who had apparently spotted their party and run away.

Reubin Fields killed a large "panther" or mountain lion near a creek they named Panther Creek, now known as Pipestone Creek. They also saw deer, elk, antelope, bear, lots of beaver dams, and many common birds. Clark wrote, "the men wer compelled to be a great proportion of their time in the water today ; they have had a severe days labour and are much fortiegued." They covered about thirteen miles and camped near a rock out-cropping locally known as Point of Rocks near the present day community of Waterloo.

Sunday August 4, 1805

Lewis's party explored the confluences of the Ruby, Beaverhead, and Big Hole rivers that together form the Jefferson. Charbonneau slowed the party down with complaints about his leg, but still they hiked more than twenty miles up and down the rivers taking notes on the best possible course forward.

Of the right fork (Big Hole) Lewis wrote, "this is a bold rappid and Clear Stream, it's bed so much broken and obstructed by gravley bars and it's waters so much subdivided by Islands that it appears to me utterly impossible to navigate it with safety. the middle fork is gentle and possesses about 2/3rds as much water as this stream. it's course so far as I can observe it is about S.W., and from the opening of the valley I believe it still bears more to the West above. It may be safely navigated. it's water is much warmer than the rapid fork and it's water more turbed ; from which I conjecture that it has it's sources at a greater distance in the mountains and passes through an opener country than the other. under this impression I wrote a note to Capt Clark, recommending his taking the middle fork p[r]ovided he should arrive at this place before my return, which I expect will be the day after tomorrow. this note I left on a pole at the forks of the river" Lewis saw no fresh signs of Indians, but commented that, "the Indians appear on some parts of the river to have destroyed a great proportion of the little timber which there is by seting fire to the bottoms." They camped on the Big Hole for the night.

Lewis compared reports with Clark a few days later, before finishing his journal entry, and added this note about Clark's trip up river, "the river continued to be crouded with Islands, rapid and shoaly. these shoals or riffles succeeded each other every 3 or four hundred yards ; at those places they are obliged to drag the canoes over the stone there not being water enough to float them, and between the riffles the current is so strong that they are compelled to have c[r]ecourse to the cord ; and being unable to walk on the shore for the brush wade in the river along the shore and hawl them by the cord ; this has increased the pain and labour extreemly ; their feet soon get tender and soar by wading and walking over the stones. these are also so slipry that they frequently get severe falls. being constantly wet soon makes them feble also."

The injury on Clark's ankle worsened, such that he was unable to walk. Clark and his men camped on the west side of the river (at a site that is now on the east side) across from the present day town of Silver Star.

Monday August 5, 1805

Due to Charbonneau's bad leg, Lewis sent him and Sergeant Gass seven miles overland to a grove of tall trees on the middle fork (Beaverhead River), while he and Drouillard scouted farther up the right fork and climbed a high point where they could look out across the valley toward today's town of Dillon. From there they proceeded overland back to the middle fork, but Drouillard fell, badly spraining his finger and injuring his leg. After a rest, they continued to the river and were glad to quench their thirst. Lewis found a well established Indian trail, but without any fresh signs on it. They traveled downstream and arrived in the dark where they were supposed to meet Charbonneau and Gass, but the men were not there. They had gone to the wrong grove, and Lewis and Drouillard had to walk another three miles downstream in the dark to find them, covering a total of about twenty-five miles for the day. They camped a few miles upstream from present day Twin Bridges.

Downriver, Clark was having a more difficult time, as Lewis noted in his journal, "the river today they found streighter and more rapid even than yesterday, and the labour and difficulty of the navigation was proportionably increased, they therefore proceeded but slowly and with great pain as the men had become very languid from working in the water and many of their feet swolen and so painfull that they could scarcely walk."

In the afternoon they arrived at the confluence of the rivers, but a beaver had cut down the note left by Lewis to take the middle fork, so Clark took the right fork, which seemed like the larger, more westerly route to follow. The crew ascended the river about one mile with great difficulty, at times cutting a passage through the willows to drag the canoes through. They camped on a muddy island where they had to make beds of brush to keep dry. Lewis later wrote, "Capt. Clarks ankle is extremely painfull to him this evening ; the tumor has not yet mature, he has a slight fever. The men are so much fortiegued today that they wished much that navigation was at an end that they might go by land."

Tuesday August 6, 1805

Having nothing to eat, Lewis and his small party spread out to look for game on their way back downriver, as well as to watch for Captain Clark and the rest of the expedition. Drouillard found the expedition first, and told Clark about the route up the middle fork. They paddled back downstream to the confluence, but tipped a canoe on the way, soaking all the baggage and a medicine box. Two of the other canoes were completely filled with water on the way down, their contents also soaked.

Joseph Whitehouse was thrown from a canoe in the rapids losing his shot pouch and horn. Lewis wrote, "the canoe had rubed him and pressed him to the bottom as she passed over him and had the water been 2 inches shallower must inevitably have crushed him to death. Our parched meal, corn, Indian preasents, and a great part of our most valuable stores were wet and much damaged on this ocasion." The entire expedition camped together on a gravel bar at the confluence where there was an abundance of firewood. Lewis wrote, "here we fixed our camp, and unloaded all our canoes and opened and exposed to dry such articles as had been wet. A part of the load of each canoe consisted of the leaden canestirs of powder which were not in the least injured, tho' some of them had remained upwards of an hour under water."

Three deer hides left high in a tree near the confluence were missing, presumably taken by a mountain lion. The hunters went out and brought back three more deer and four elk to feed the expedition. George Shannon had been sent upriver to hunt in the morning, before the canoes turned around. He did not come back to camp.

Lewis and Clark named each fork of the river, retaining the name Jefferson River for the middle fork, which is today known as the Beaverhead River. In commemoration of virtues, they named the left fork the Philanthropy (now known as the Ruby River) and the right fork as the Wisdom River (now known as the Big Hole.)

Wednesday August 7, 1805

Lewis sent Reubin Fields in search of Shannon. The expedition rested and dried their gear. Having consumed much of their supplies, they stowed one canoe in a thicket of brush, and consolidated the gear into the remaining canoes.

Lewis fixed his gun and made navigational observations as well as he could under cloud cover. By early afternoon the expedition was again underway, headed up the middle fork. An abundance of large and small biting flies more than made up for a reduced number of mosquitoes. The expedition traveled a few miles and camped just upstream from present day Twin Bridges. Lewis wrote, "we have not heard any thing from Shannon yet, we expect that he has pursued Wisdom river upwards for some[e] distance probably killed some heavy animal and is waiting for our arrival."

This was the second time Shannon had been separated from the group. Back on the lower Missouri he had been lost for fifteen days, and subsisted entirely on wild grapes for nine of those days.

Drouillard brought in a deer in the evening. Clark noted that "all those Streams Contain emence number of Beaver orter Musk-rats &c." An afternoon thundershower poured down rain for about forty minutes.

Thursday August 8, 1805

Lewis wrote, "We had a heavy dew this morning. as one canoe had been left we had no more ha[n]ds to spear for the chase ; game being scarce it requires more hunters to supply us." Reubin Fields returned at noon, reporting that he had been up the right fork as far as the mountains and could find nothing of Shannon. Fields and some of the other hunters killed a few deer and antelope. Lewis reported, "t[h]e tumor on Capt. Clarks ankle has discharged a considerable quantity of matter but is still much swolen and inflamed and gives him considerable pain."

Lewis noted, "the Indian woman recognized the point of a high plain to our right which she informed us was not very distant from the summer retreat of her nation on a river beyond the mountains which runs to the west. this hill she says her nation calls the beaver's head from a conceived re[se]mblance of it's figure to the head of that animal. she assures us that we shall either find her people on this river or on the river immediately west of it's source ; which from it's present size cannot be very distant. as it is now all important with us to meet with those people as soon as possible I determined to proceed tomorrow with a small party to the source of the principal stream of this river and pass the mountains to the Columbia ; and down that river until I found the Indians ; in short it is my resolusion to find them or some others, who have horses if it should cause me a trip of one month. for without horses we shall be obliged to leave a great part of our stores, of which, it appears to me that we have a stock already sufficiently small for the length of the voyage before us." The entire expedition camped a few miles downstream from Beaverhead Rock.

Shannon caught up with the group the following day and reported that he had come down the right fork to the point where he left the expedition, and not finding them, traveled back upriver a considerable distance in search of them. He brought back three good deerskins and had eaten plenty, "but looked a good deel worried with his march." Lewis noted.

Sacagawea recognized Beaverhead Rock along the Beaverhead River as the home of her people.

The Shoshone

Clark continued upriver with the canoes and most of the crew, while Lewis and a handful of men hiked ahead in search of Sacagawea's people. The Shoshone were frequently attacked by the better-armed Blackfoot Indians, so they were naturally cautious and ran away when approached. They had heard about, but never seen a white man before.

Lewis and his men hiked up to the continental divide, standing on the border between today's Montana and Idaho. With the Missouri River watershed behind them and the Columbia watershed ahead of them, they hoped to find a navigable route to the Pacific, but instead saw mountain ranges as far as the eye could see. Ten miles later they encountered three Shoshone women, and caught up with two of them, who sat down on the ground, apparently resigned to their fate of being either captured or killed. Lewis gave them gifts and convinced them to take them back to their camp. On the way they met sixty Shoshone warriors on horseback. The women showed them the gifts Lewis provided, and the chief, Cameahwait, dismounted and gave Lewis a hug. Lewis convinced the Shoshone to come back with him to meet Clark and to help bring the rest of the gear on horseback to their encampment.

They met Clark and the crew on the Beaverhead River. Sacagawea was brought in to assist as an interpreter and recognized Cameahwait as her older brother. She leapt up and threw her arms around him. The Shoshone helped transport the expedition's gear back to their camp.

With Sacagawea's help, Lewis and Clark were able to trade for horses and hired a guide to help them cross the mountains to navigable waters on the other side. Still, the mountains were steep and dangerous. They were caught in a heavy September snowstorm, and there was so little food in the mountains that they nearly starved. On the other side they traded for food from the Nez Perce of today's northern Idaho. The salmon and camas root diet did not sit well with hard-working men who were accustomed to eating eight or nine pounds of red meat a day. Most of the men got sick.

Lewis and Clark negotiated with the Nez Perce to take care of their horses for the winter. They made new dugout canoes and continued the journey down the Clearwater, Snake, and Columbia rivers to the Pacific, at times shooting rapids so dangerous that local Indians lined the banks to watch the crazy white men get killed.

They built Fort Clatsop a few miles from the ocean and stayed there for the winter, frequently trading or entertaining with the Indians. They spent much of the winter boiling seawater to get a supply of salt. The coast was a miserable, constantly rainy place to stay, and their fort was full of fleas, but they found adequate food supplies, mostly elk, and made it through the winter.

Rattlesnake seen in the Jefferson River Canyon.

Clark's Return Trip Down the Jefferson River

In the spring of 1806, the Lewis and Clark expedition started home, dragging their canoes back up the Columbia River towards the Rocky Mountains. The Nez Perce returned their horses to them, and when the snow melted sufficiently near the end of June, the Corps of Discovery crossed back over the mountains. Lewis and part of the expedition explored a northerly route back to the Missouri, while Clark and the rest of the party returned to the canoes they had cached by the river the previous fall. They recovered the canoes and proceeded down the Beaverhead River to the Jefferson and back down to the confluence with the Madison and Gallatin Rivers near present day Three Forks. They kept the horses, with part of the crew traveling overland, while others canoed down the river. Paddling downstream proved to be much easier than going up!

Thursday July 10, 1806

Clark wrote, "last night was very cold and this morning everything was white with frost and the grass stiff frozend. I had some water exposed in a bason in which the ice was 3/4 of an inch thick this morning. I had all the Canoes put into the water and every article which was intended to be sent down put on board, and the horses collected and packed with what fiew articles I intend takeing with me to the River Rochejhone (Yellowstone River)"

The expedition covered fiften miles down today's Beaverhead River by noon when they stopped to let the horses graze. Along the way, Clark saw deer, antelope, rattlesnakes, and fifteen big horn sheep. He wrote, "Sergeant Ordway informed me that the party with him had come on very well, and he thought the canoes could go as farst as the horses" Indeed, on this day, the canoes passed by six of their campsites from their struggle upriver a year before.

Clark summed up the afternoon, "the Musquetors were troublesom all day and untill one hour after Sunset when it became cool and they disappeared. in passing down in the course of this day we saw great numbers of beaver lying on the Shores in the Sun. wild young Gees and ducks are common in the river. we killed two young gees this evening. I saw several large rattle snakes in passing the rattle Snake Mountain they were fierce."

Friday July 11, 1806

"Sent on 4 of the best hunters in 2 canoes to proceed on a fiew miles a head and hunt untill I came up with them, after an early brackfast I proceeded on down a very crooked chanel, at 8 a.m. I overtook one canoe with a Deer which Collins had killed, at Meridian passed Sergt. Pryors camp near a high point of land on the left side which the Shoshones call the beavers head. the wind rose and blew with great violence from the S W immediately off Some high mountains covered with Snow. the violence of this wind retarded our progress very much and the river being emencely crooked we had it immediately in our face nearly every bend."

By six p.m. they passed the Beaverhead's confluence with the Philanthropy (Ruby) River, and an hour later they reached the confluence with the Wisdom (Big Hole) River where they camped for the night. A bayonet and the extra canoe left behind last year were found undisturbed. Clark ordered the men to recover all the nails from that canoe and another they were leaving behind and to make paddles from the wood.

George Gibson and John Colter killed a fat buck and five nearly grown geese. Sergeant Pryor shot a deer and left it by the river. He proceeded on downriver with the horses and did not camp with Clark.

Saturday July 12, 1806

By 7 a.m. the men finished recovering the nails and making paddles. They ate breakfast and headed downriver, finding the current stronger and the river straighter than upriver, but they still had to battle the wind. A sudden puff of wind drove Clark's canoe under a log overhanging the river, pinching Thomas Howard between the log and the canoe. The canoe was nearly overturned, but they freed themselves before the rest of the party could make their way through the brush along the river to help them. By 3 p.m. they were all the way down to Field's Creek (the Boulder River) where they stopped to eat and camp. Alexander Willard and John Collins brought in two deer.

Sunday July 13th, 1806

Clark and his men started paddling early and reached the three forks of the Missouri by noon. Sergeant Pryor and the party with the horses arrived there just one hour earlier. They had killed six deer and a grizzly bear.

Clark sent Sergeant Ordway and some of the men with the six remaining canoes to meet Lewis downstream at the confluence of the Missouri and Marias Rivers. Meanwhile, Clark took Sergeant Pryor, Joseph Shields, George Shannon, William Bratton, Francois Labiche, Richard Windsor, Hugh Hall, George Gibson, Charbonneau, Sacagawea, Pomp and Clark's slave York, along with the forty-nine horses, overland through the Gallatin Valley to explore the Yellowstone River route back down to the confluence with the Missouri near the present day Montana-North Dakota border. The horses were stolen along the way, but they made boats and floated down the Yellowstone.

Lewis and Clark met up again on the Missouri River just downstream from its confluence with the Yellowstone, shortly after Lewis had been shot in the buttocks by one of his own hunters. Lewis was confined to the canoe to recover for most the remaining journey back to St. Louis, but he was on his feet again when they arrived. All were treated to a hero's welcome.

References:

"Headwaters Target of European Exploration." The Headwaters Herald. Montana Fish, Wildlife & Parks.

Moeller, Bill and Jan. Lewis & Clark: A Photographic Journey. Mountain Press Publishing Company: Missoula, Montana. 1999.

Ambrose, Stephen E. Undaunted Courage. Touchstone: New York, NY. 1996.

See Also The Jefferson River Canoe Trail Overview

and Floating the Jefferson River Canoe Trail

Jefferson River Chapter LCTA

PO Box 697

Pony, MT 59747

Contact Us

Become a Member

Join us today!

The canoe trail was featured in the May 2014 National Park Service Lewis & Clark newsletter, The Trail Companion:

|

Jefferson River Chapter Membership: Join us Today!

Jefferson River Chapter Membership: Join us Today!